Home & Design Cover - John Blee

Janice Jakielski - Exposure Magazine

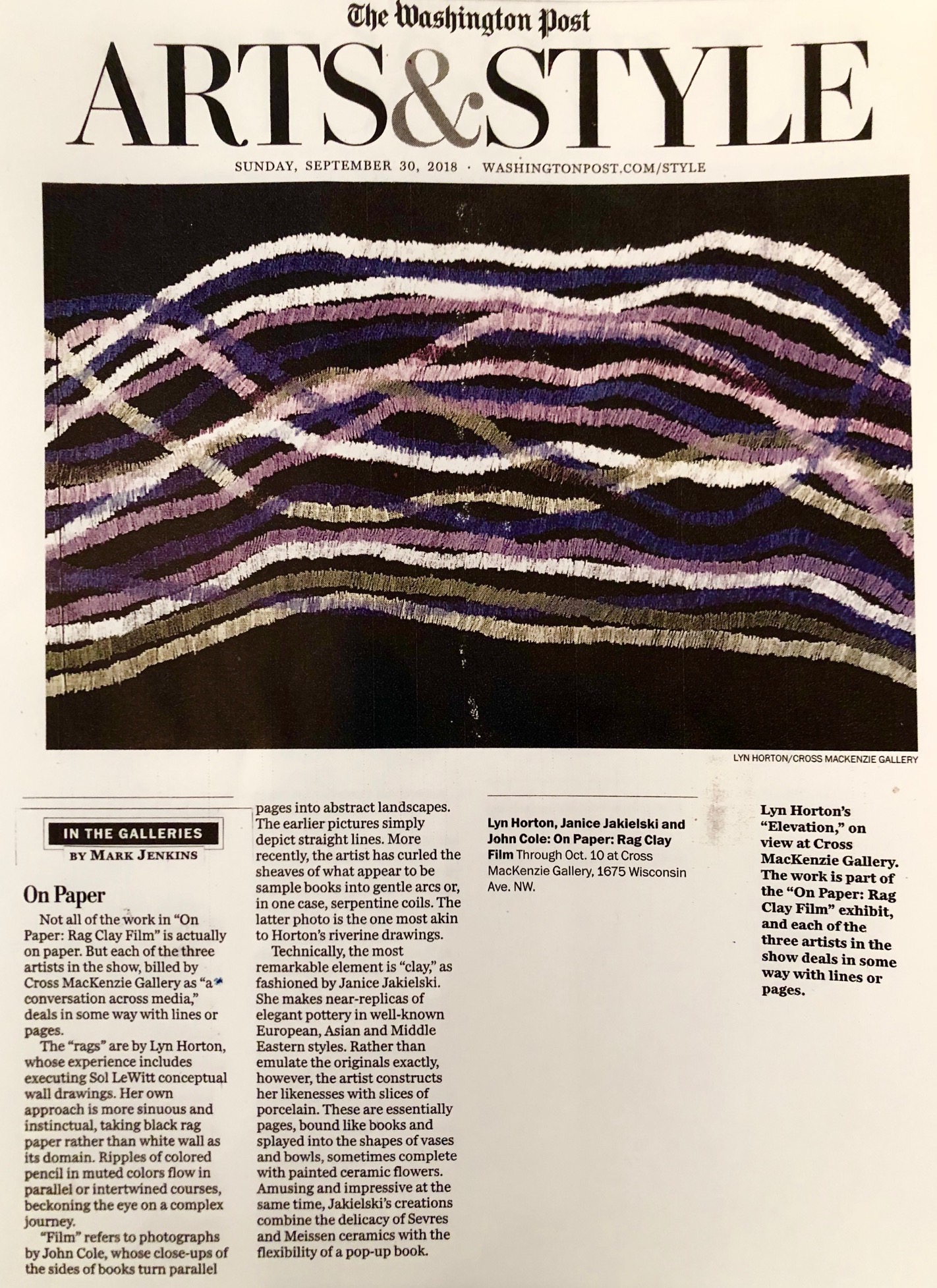

On Paper - The Washington Post, In The Galleries →

Zeke Named "Best Gallery Dog" by The Washington City Paper

Photograph courtesy of Darrow Montgomery

By Stephanie Rudig

D.C. is full of smaller galleries and arts spaces that are showcasing interesting stuff. In the midst of Georgetown galleries peddling above-the-couch fare, Cross MacKenzie has always been a diamond in the rough, featuring outstanding and interesting work from established and up-and-coming artists. Also setting them apart from the rest of the pack is their beloved gallery dog, Zeke, who belongs to gallery owner and artist Rebecca Cross. Zeke got his start hanging out in the gallery window, and has since become emboldened to act as guard dog, occasionally barking an alert that people are about to enter. Zeke makes for a great gallery companion, following visitors around as they take in the excellent art. Fair warning to dog lovers who are rushing out to Cross MacKenzie as they read this: For the sake of work-life balance, Zeke only comes in a few times a week, usually earlier in the week, and spends the rest of his time chasing deer out in the country.

Destination Hillsboro - Home & Design →

Click on the title to read the rest of the article.

Read moreRebecca Cross - By George: Stories of Georgetown Blog, August 2017

ON HIS DEATHBED, REBECCA CROSS’ FATHER HAD AN UNUSUAL REQUEST. HE WANTED HER TO MAKE HIM AN URN.

‘My father was an architect but he’d started taking ceramics classes, and he made an urn for my mother when she died,’ says Rebecca, the owner of Cross MacKenzie Gallery in Book Hill.

Rebecca put her own art on hold for a decade to run the gallery, but the death of both parents last year forced her to start thinking about—well, death. She began drawing again, creating a series of abstracted, ancient weapons from around the world that signify objects as agents of death.

On September 8, her drawings will be featured in a new exhibition called Termini—a conversation on death, both symbolic and physical. Rob Barnard and British artist Julian Stair’s powerful cinerary jars will also be on display, one of which Rebecca says she’ll likely purchase for her father.

‘I think they’re architectural enough that he’d approve. I’ll make his urn symbolically by bringing them together.’

Rebecca’s life and art have always been one in the same. Growing up in Virginia, she took classes at the Art League in Old Town Alexandria and lived in the mid-century modernist community of Hollin Hills—a neighborhood her father helped design.

‘My Dad really shaped my views. I was steeped in his aesthetic,’ says Rebecca, whose own husband, Max, is an architectural photographer. ‘My parents took my art very seriously because aesthetics, art and design were their business, too. It was never thought to be a waste of time or frivolous.’

As a child, Rebecca frequently redecorated and painted her bedroom—going so far as to paper mache the doorknobs. In high school, she made furniture out of old broom sticks, and had a printmaking internship at the National Collection of Fine Arts, followed by a summer serving as the assistant to a jeweler in the Virgin Islands. She painted, she sculpted, she combed a Husky so she could spin the hair for weaving.

‘I just had so much exposure to art. I was lucky.’

After graduating from Bennington College, Rebecca got her MFA in painting at the Royal College of Art in London. She lived there for six years, renovating a warehouse in an artist’s community on the Thames and working for sculptor Sir Anthony Caro.

For years, Rebecca painted and made ceramics—showing and selling her work everywhere from Georgetown’s Addison/Ripley to Barney’s New York and Japan. She also designed the sets and costumes for Bresee Dance Company in Norway, whose production of Unstill Lives was performed at the Kennedy Center, and for Tony Williams’ BalletRox production of The Urban Nutcracker--still running in Boston after 17 Christmas seasons.

In addition to her own career, Rebecca acted as an agent for her husband, Max, whom she’d met at 18.

‘I worked on getting him shows and grants, and in the magazines. We were a partnership. I’d been dealing with his galleries and my galleries for years, and opening our own just seemed like something that we could do. It seemed like a new chapter.’

In 2006, Rebecca opened Cross MacKenzie Gallery in Canal Square. Her initial focus was on ceramics, but it was too narrow a niche. She expanded her gallery and moved to a space in Dupont Circle.

Three years ago, Margaret Heiner was moving her Book Hill gallery to Connecticut and the space became available. Rebecca and Max jumped at the chance, partnering with her sister and brother-in-law to purchase the building.

As one of six galleries that comprise the Georgetown Galleries on Book Hill collective, Cross MacKenzie now features emerging and mid-career artists with high-quality, (mostly) one-of-a-kind artwork.

‘They aren’t big names but they all went to art school and are extremely talented,’ Rebecca says. ‘I know many of them through being an artist myself for so many years. One artist will lead me to another artist.’

Pieces range from Rebecca’s own ceramics to her husband’s photography and others’ paintings.

‘I like showing ceramics with the paintings that would be above them, like when you actually live with your art. I really enjoy curating the collections together and hanging a two-dimensional thing behind a three-dimensional thing. They set each other off.’

Rebecca’s customers range from passersby who fall in love with a piece in her window, to collectors, architects, and interior designers. Although most skew older, Rebecca makes a conscious effort to showcase a few smaller, more affordable pieces that are more attainable for young professionals.

‘I love sharing the art and talking to everyone who comes in,’ she says. ‘I really enjoy the shopkeeper aspect of running the gallery. I love planting my flowers out front, getting my coffee and croissants from Patisserie Poupon. I already did edgy when I was young, living in a marginal community in London with a bunch of first-wave artists. We loved it, but it was dangerous. There were murders on the street! Now I’m this age, and it’s lovely to be part of such a nice community.’

While Georgetown serves as Rebecca’s daytime base, her family recently purchased a home in Hillsboro, Virginia, that was built in 1789. They’re no strangers to such lofty projects, having already renovated a schoolhouse in Minnesota that Max had photographed for years. They purchased the property 15 years ago, moved it nine miles, and knocked out the fourth wall to accommodate floor-to-ceiling windows. Over 500 of Rebecca’s hand-painted tiles adorn the home, each an homage to their life in the country.

‘Our life and everything we do—every project—are woven together,’ says Rebecca, whose sons are also in the arts—one as a filmmaker in LA, the other a painting student in New York. ‘I’ve had all of these stages in my life. My life as a painter, my life as a mother, my life as a gallery owner. This next chapter is my life in the country. I’m trying to put those last two chapters together.’

As Rebecca prepares for her upcoming Termini show—a reflection on the final chapter in every life—she says her weapons series has sparked her imagination.

She already has an idea of what she wants to do next.

See more here.

Midnight in the Clearing - The Washington Post, In the Galleries

In the galleries: Canadian artist looks to the outdoors for inspiration

By: Mark Jenkins

At the opening of Patrick Bermingham’s Cross MacKenzie Gallery show, “Midnight in the Clearing,” the attendees were plunged briefly into darkness. With the lights switched off, the Canadian artist discussed his technique and humans’ underappreciated ability to see at night. Artificial illumination is so widespread, he said, that “we’ve forgotten we have these primeval skills.”

Bermingham’s pictures are far from primeval, but they’re not exactly trendy. The artist paints with oils, most often on wood panels, in a nocturnal palette of gray, black and hushed greens, sometimes set off by a deep-blue sky. The show’s largest piece even forgoes the greens. Ten feet wide and monochromatic, “Study for Midway on Our Path” immerses the viewer in both night and woodland.

The artist hauls panels large enough to make such pictures into the forest, where he paints from the vantage point he wants the spectator to experience. Many of the locations are in Ontario — Bermingham doesn’t seem drawn to the topographical drama of the mountain West — but this selection also includes smaller-scale pictures made in Guatemala.

Read more here.

Cross MacKenzie's Last Picture Shows on Book Hill - The Georgetowner →

By: Richard Selden

In the front room of Cross MacKenzie Gallery, at 1675 Wisconsin Ave. in Georgetown, is a lime-green tangle of a ceramic sculpture on a pedestal: “Spirulina” by Tyler Lotz. Named for the beneficial microalgae that some add to smoothies, it is the conversation-starting centerpiece of the gallery’s current “Best Of” retrospective, featuring more than a dozen mostly large, mostly bright-colored contemporary paintings and photographs.

Cross MacKenzie will mount just one more show at its bay-windowed Book Hill location, a solo exhibition of new “Night Paintings” by Canadian artist and entrepreneur Patrick Bermingham. Co-owners Rebecca Cross and her husband, architectural, aerial and fine-art photographer Maxwell MacKenzie, are relocating the gallery to their new home in Hillsboro, Virginia.

To read more, click on the title of the article.

Stratum - The Washington Post, In The Galleries →

Geankoplis, Miller and McInturff by: Mark Jenkins

Usually, the glazes and slips that overlay pottery are thin and become fused with the object during firing. Ceramicist Nick Geankoplis takes a different approach to layering in Cross MacKenzie Gallery’s “Stratum.” His wall-mounted pieces contrast chunky, bright-colored drips with black images of traditional Chinese and contemporary globalist icons.

Geankoplis works and teaches in Kansas, but spent four years in Beijing. That sojourn prompted ceramics that are both minimal and busy. Fitted into gold frames, the pieces are white planes that are empty save for areas covered by the dripped glazes. That’s where the artist places the transferred Chinese decorative motifs and an occasional Western corporate logo. The technique is intriguing and risky: This show was supposed to have included a larger selection, but only three survived the firing process.

“Stratum” also features several photo collages by Steve Miller, whose work was shown at the National Academy of Sciences this year. Miller combines X-rays of animal skeletons with aerial photography of the Amazon rain forest to make pictures of endangered nature that are rich visually and metaphorically.

In addition, the gallery is showing “Summer Fresh,” ceramics by Marissa McInturff that are more functional than Geankoplis’s work. The flowerpots and similar items are in sunny or earthy Mediterranean hues — McInturff is based in Barcelona — and made of stackable pieces. All are small in scale, yet in shapes that suggest towers and spires. Grouped together, the vessels resemble a miniature city.

Nick Geankoplis and Steve Miller: Stratum and Marissa McInturff: Summer Fresh “Stratum” through June 30 and “Summer Fresh” through July 31 at Cross MacKenzie Gallery, 1675 Wisconsin Ave. NW. 202-337-7970. crossmackenzie.com.

Oculoire - The Washington Post

By Mark Jenkins

The photographic duo known as Oculoire has a French name and a French vibe. Ned Riley and Phil Hernandez acknowledge the influence of Brassai and Cartier-Bresson, Gallic masters from the golden age of black-and-white; their high-contrast pictures also recall France’s film-noir and New Wave cinema. But the two collaborators, who don’t specify who does what, use skateboards rather than jetliners to reach their locations. The futuristic vista that’s the centerpiece of the team’s self-titled Cross MacKenzie Gallery show suggests a still from Godard’s “Alphaville,” but it actually depicts the supports of the Woodrow Wilson Bridge.

That photo takes an upward view, which is common in Oculoire’s work. The duo calls its style “street photography,” but the street is often less a subject than a vantage point for gazing up or sideways — frequently into the deep blacks of shadow or night. Oculoire uses both electronic and film formats, but the goal is make pictures that appear to predate digital imagery. Staring into the darkness is a means of stepping into the past.

Read more here.

Oculoire - Washington City Paper

By Louis Jacobson

Phil Hernandez and Ned Riley met more than a decade ago at D.C.’s Gonzaga College High School. It’s a history that gets a hat-tip in the duo’s photo exhibition at the Cross MacKenzie Gallery via the purple-and-white color scheme on the gallery’s walls. Hernandez and Riley have teamed up as Oculoire, a collaborative effort to produce black-and-white photographs that are heavily focused on D.C., from monumental columns to Metro stations. The name is a portmanteau of “oculus,” or eye-shaped form, and “neo-noir,” for the moody vibe they’re attempting. The pair frequently spotlight tunnels, cobblestones, and mopeds. Through the images a story emerges, one of the city’s gritty elegance, from the hum of D.C.’s everyday skateboarding culture to late nights in alleyways. It’s a romanticized vision of life in the city, but one that also manages to ring true.

Read more here.

Andrea Ponsi "Face it!" - Abitare Magazine

By Matteo Zambelli

Andrea Ponsi is a Florentine architect who dedicates equal attention to architecture, design, painting, writing and teaching. It’s no coincidence that in 1974 he received his architecture degree in Florence with Leonardo Savioli (the centenary of whose birth is this year), master of an approach that crosses over disciplinary borders. Ponsi’s activities as a painter are spread out across different areas of research. The first is that of the scores-notes, a form of automatic writing organised into musical scores that hybridise imaginary graphemes, mythical symbols, fields of colour and flashes of architecture to create an emotional diary capable of condensing memories and feelings without recourse to words. Another area of research is dedicated to perceptive maps and urban landscapes, or rather subjective explorations within the fabric of cities told through a combination of site plans, elevations, cross-sections, perspectives (the architect’s tools for representation) with landscape painter-like watercolours. The result of these, apart from paintings, are two books that feature as protagonists both in pictures and in words the cities of Florence and San Francisco. Then there’s the research dedicated to analogous cities, in which Ponsi shows through sketches and drawings how using architectural references and the cities of the past it’s possible to conceive of a new architecture or a new urban layout using the tool of the analogy, theorised by the Florentine author in two educational books that reveal his teacher’s soul. The Cross MacKenzie gallery in Washington DC displays Ponsi’s last area of experimentation, that of faces drawn on Post-its.

When Andrea talks on the phone he has the compulsive habit of sketching (with a pencil, a pen or whatever he has to hand) completely invented faces that have nothing to do with the person at the other end of the line. He can’t give a reason for this impulse, the only explanation that he hazards, in the form of a question, is that it could have something to do with the typically Italian tendency (masterfully explored by Bruno Munari in the Dizionario dei gesti degli italiani, or Dictionary of Italian Gestures) of gesticulating with our hands when speaking. Once the call finished Andrea Ponsi would throw away the Post-its, but one day an assistant (who had been picking them out of the bin) lined them all up so he could see them next to each other, surprising Ponsi with the human menagerie that he had drawn over time.

Ever since then (this happened in the 1990′s) he began to collect them and today he’s sketched nearly 20,000 faces: an entire city. A city with one particularity: all the faces are male because, he explains, “I wouldn’t want to draw an angry, monstrous, silly or grotesque woman”.

Read more here.

Andrea Ponsi "Face it!" - Washington Post, In The Galleries

By Mark Jenkins

Among the perplexities of our age is that art is becoming less durable and kitsch more so. Artists intentionally work with stuff that won’t last — plants, ice, light, cardboard — while computer memory allows snapshots and cute-animal videos to endure (theoretically, at least) forever. Italian architect Andrea Ponsi’s sketches, on display in “Face It!” at Cross MacKenzie Gallery, combine aspects of the eternal and the disposable: They’re rendered with neoclassical technique on Post-it notes.

The gallery is papered with about 2,000 Ponsi drawings, each of a face the architect says is imaginary. Nearly all are on small squares of yellow paper, some in a brighter shade. (These are an off-brand.) Most are in a single color, usually black or red, but some are in multiple hues. About 70 of the drawings are on larger sheets. The bigger ones are in charcoal; the smaller ones also employ pencil, ink and occasionally paint.

Ponsi may not portray actual people, but that doesn’t mean there are no sources for his pictures. The architect grew up in Tuscany and attended college in museum-rich Florence, where he’s based. The stylistically diverse sketches range from realistic to playful and indicate a familiarity with both Old Masters and the New Yorker.

Lined up neatly together, the drawings also suggest Warhol and other modernists who embraced mechanical reproduction. It’s only the format of Ponsi’s sketches, however, that’s repeated. Every visage is different, which makes “Face It!” a small act of rebellion against mass-produced culture.

Read more here.

William Dunlap - The Washington Post, In the Galleries

A fine example of William Dunlap’s “Southern (ir)Reverence” is the title of his series of mixed-media pictures of Union and Confederate uniforms. He calls them “Brand Loyalty,” undercutting any claim that a preference for gray rather than blue is a reasoned position. For many, it’s more like favoring Pepsi over Coke, suggests the artist in this playful show at Cross MacKenzie Gallery.

Working on paper rather than canvas, Dunlap depicts the empty suits of the 1860s with accuracy, but also with confident looseness. Dollops of gold leaf represent buttons, and the uniforms and backdrops are personalized with drips, spatters and strokes of crayon and charcoal. The Virginia artist gives a similar treatment to dogs, a saber and two sweeping landscapes dominated by agricultural/industrial buildings. These handsome views exemplify Dunlap’s method in this show: epic yet intimate, simultaneously precise and free. Also available is Dunlap’s “Short Mean Fiction,” a limited-edition book of text and drawings; each copy includes a set of original prints.

New Material - The Washington Post, In The Galleries

In the galleries: In two exhibitions, three painters put aside their brushes By: Mark Jenkins November 9

The impromptu brushstroke was so emblematic of abstract expressionism that pop artist Roy Lichtenstein parodied it for decades. But some mid-20th-century abstraction shunned brushes altogether in favor of pouring, dripping and spattering. That such techniques are still fruitful is confirmed by the work of three artists, Greg Minah, Nicole Gunning and Shar Coulson, at two shows a block apart.

Cross MacKenzie Gallery’s “New Material” reflects how Minah and Gunning add water and clay, respectively, to the mix. Minah pours pigment and, while it’s still liquid, spins the canvas to cause gestures that flow and crisscross each other. Sometimes he sprays the surface with water or air, partly removing the paint but leaving ghostly outlines where the edges of the rivulets have dried. These can stand alone or serve as bones to be overpainted with layers of multicolored skin.

Nicole Gunning’s “Kelp Forest.” (Nicole Gunning/Cross Mackenzie Gallery)

The Baltimore artist has undertaken several variations on this strategy. Some of the resulting pictures are pastel and chalky, and others are brighter and more opaque. The most recent work features textures that appear feathery, as though the intricate overlaps were still fluttering. Minah freezes streams of paint, but the sense of motion remains.

Primarily a ceramist, Gunning has previously shown her terra-cotta nude self-portraits. Currently without access to a kiln, the D.C. artist has turned to splashing colored bentonite on canvas. The 3-D clay affixes in patterns that resemble coral reefs, lichen-covered rocks or, as one title has it, a “Kelp Forest.” Although a single-color undercoat holds the entirety together, the colors and clumps are strikingly unpredictable.

The mixed-media paintings of Shar Coulson, whose “Perception vs. Reality” is at Artist’s Proof, are somewhat more traditional. The Chicago artist’s work begins as abstract but comes to include hints of nature and landscape imagery. (Her current series is titled “Fauna Flora Figure.”) Some brushwork is evident amid the strata of wax and acrylic paint, as are lines drawn in charcoal.

Yet Coulson uses tactics akin to Minah’s. She regularly rotates the canvas so as to approach the composition from fresh perspectives. Also, she abrades pigment she has applied, both to yield weathered textures and to open areas for new forays. The completed pictures feel delicate yet physical, combining muted hues and robust gestures. Coulson’s homages to flora and fauna are just as much celebrations of the act of painting.

Greg Minah and Nicole Gunning: New Material Through Nov. 14 at Cross MacKenzie Gallery, 1675 Wisconsin Ave. NW.

Richard Schur - Luxe Magazine

We are so proud of Richard Schur for being featured on the cover of Luxe magazine. Gorgeous!

Walter McConnell - CFile, June 2017

American sculptor Walter McConnell explores the West’s near-fanatical fascination with blue- and-white Chinese porcelain from the 1870s through today in his installation Chinamania (July 9, 2016–June 4, 2017) at Arthur M. Sackler Gallery.

A mania for Chinese blue-and-white porcelain swept through London in the 1870s as a new generation of artists and collectors ‘rediscovered’ imported wares from Asia. Foremost among them was American expatriate artist James McNeill Whistler. For him, porcelain was a source of serious aesthetic inspiration. For British shoppers, however, Chinese ceramics signified status and good taste. Cultural commentators of the time both embraced and poked fun at the porcelain craze. Illustrator George du Maurier parodied the fad in a series of cartoons for Punch magazine that documented what he mockingly called “Chinamania.”

More than 150 years later, American artist Walter McConnell explores Chinamania in our own time. In his exhibition, he juxtaposes two monumental porcelain sculptures, which he terms stupas – Dark Stupa and White Stupa, with 3D printed replicas of blue-and-white export wares from China’s Kangxi period (1662–1722) — similar to those that once filled the shelves of Whistler’s Peacock Room in London.

McConnell’s interest in replication and in the serialized mass production of ceramic forms began after he visited China more than a decade ago. The large kilns and busy factories at Jingdezhen prompted McConnell to look at China as an enduring resource for ceramic production.

Chinamania complements the exhibition Peacock Room REMIX: Darren Waterston’s Filthy Lucre, a contemporary installation that reimagines the Peacock Room as a resplendent ruin. Inspired by museum founder Charles Lang Freer’s collection of Asian ceramics, Waterston painted scores of vessels and arranged them on the buckling shelves of Filthy Lucre. These oozing, misshapen ceramics convey a sense of unsustainable luxury and excess. They also echo McConnell’s interest in the interplay of creativity, the mass production of aesthetic objects, and the powerful forces of materialism and conspicuous consumption.

Read more here.

Michele Mattei "First Ladies" - L'Oeil de la Photographie

The First Ladies exhibition at the Cross MacKenzie gallery follows the success of Fabulous, a four month solo show at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington DC. Both projects were created from a series I developed over the past fifteen years on extraordinary women who made significant contributions in the fields of arts, sciences, social justice. It is titled The Rebel Age and is part of a forthcoming book project.

We are in a time of necessary changes and today more than ever before it is vital that we share the lives, the strength and the wisdom of these extraordinary women. They are a source of inspiration and are as relevant today as they always were. They have shaped the world we live in. They fought for women’s suffrage, reproductive rights, equal pay and stood against sexual harassment, and violence against women.

For them it was all about debunking the beliefs and the myths about women as seen for hundred of years. They came a long way. There is still a very long way to go.

Read more here.

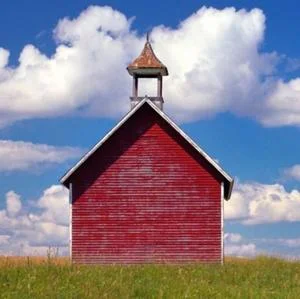

Max MacKenzie - Washington City Paper

Maxwell MacKenzie, Going Deep, Cross-MacKenzie Gallery

For the better part of two decades, D.C. photographer Maxwell MacKenzie has been photographing decaying architecture on the Great Plains, sometimes from the ground and sometimes from the air. His exhibit this year—marking the fifth time he has made our annual top 10 list—had the feel of a final exam, an intimate retrospective on the long arc of his subject matter and his career. The artist’s own Cross MacKenzie Gallery, where the exhibit was held, is cozier than many of his past venues, which enforced a less expansive approach. Instead of displaying a succession of collapsing barns linearly, as if they were lining the prairie, Going Deep focused more on matrices that emphasized the passage of time—revealing how time scars, and occasionally revives, the old structures he finds in places like rural Minnesota. Despite the initial appeal of his early experiments with infrared-sensitive black-and-white film, the monochrome photographs in this year’s exhibit literally paled in comparison to his subsequent color images.

Read more here.