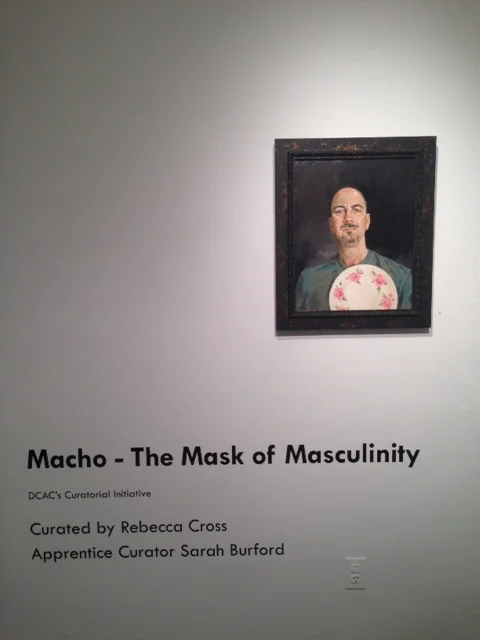

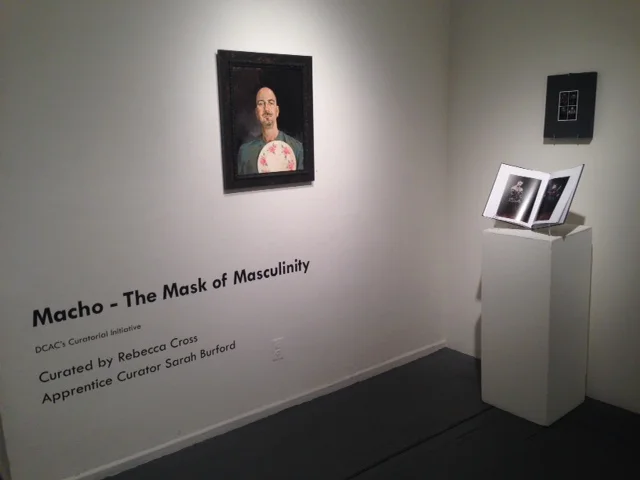

Macho - The Mask of Masculinity

Curated by Rebecca Cross

Apprentice Curator: Sarah Burford

On view at the DC Arts Center (2438 18th St, NW) April 28 - May 28

Opening Reception: Friday, April 28, 7-9 pm

Artist Talk and Closing Reception: Sunday, May 21, 5 pm

Opening Reception at Cross MacKenzie Gallery: Friday, June 9, 6-8 pm

Works by: Damon Arhos, Michael Corigliano, Hector Emanuel,

Timothy Johnson, Mark Newport, Joseph Daniel Robert OLeary,

Kate Warren, Dawn Whitmore

Definition from the Oxford English Dictionary:

macho

/ˈmäCHō/

noun

1. a man who is aggressively proud of his masculinity.

“Macho” takes as its point of departure recent debates about the role of men in contemporary society. As we began exploring ideas for this exhibition, we continuously came across examples of work showcasing people who were “projecting” an air of strength and masculinity rather than openly revealing their authentic male selves. These remarkable artists all react, in their own ways, to the promulgated notion that “masculinity” itself is not a trait that simply exists, but rather one that needs to be worn like a mask. Masks of real and imaginary uniforms, physical poses and symbolic props, aid the figures in projecting this shroud of self-aggrandizement. The concept reaches far beyond the limits of a single exhibition, but we present this provocative group of artists making engaging, surprising and challenging art around this subject as a means of furthering the existing dialogue, exposing both the disturbing and comical evocations of our title to engage with the conflicting realities of post-modern manhood.

Three thematic elements run through this exhibition of proudly projected masculinity; elements that can be externally adopted, worn or expressed - literally or figuratively – to inhabit a macho identity.

The POSES The PROPS The COSTUMES

POSES

Body language itself cues the viewer to see a figure as “aggressively and proudly masculine.” The body here is tantamount: physical superiority is central to so many stereotypically “male” traits, such as strength, bravery, physical prowess, and power. A universal pose expressing such power is with the head up, chest out and biceps lifted and flexed. This stance projecting strength and dominance, may intimidate or threaten others with implied violence; muscles are flexed in a show of warning that commands respect or fear. Conversely, the swagger of cool that demonstrates a quiet confidence, unaffected by all external forces, is an equally macho pose. Relaxed, hands in pockets or belt loops, with a preternatural calm, is a restrained act of projected masculinity in the language of the body.

Dawn Whitmore’s photograph of a female body builder demonstrates that even women can inhabit the “macho” of masculinity in her visual explorations of women’s competitive weight lifting. By empowering the body with physical strength and adopting the physicality of men, Whitmore’s subjects expose the reality that masculinity does not belong to men alone. With her proud act of display and flexed biceps, her subject’s body becomes its own macho prop.

Damon Arhos’ oversized canvas ”Pomp” parodies the spectacle of the macho power pose. Arhos shows an un-athletic, regular guy flexing his biceps - and in so doing, comically deconstructs the stance when there are no muscles to back up such a display of dominance. The masked figure, weak in a rumpled T-shirt, bald and beardless standing in front of an unspecified continent and presiding over a networked, connected landscape, may be making the point that to dominate the world in the current technological sphere, the nerd needs brain, not brawn. Leaders like Mark Zuckerberg and Steve Jobs project power through their convention-shattering collarless shirts and hoodies, eschewing the rugged outdoorsman image, and like the man in “Pomp,” sporting pasty indoor physiques.

In photographs from her “All Dudes all Nudes” series, Kate Warren’s men adopt that macho pose with bulging biceps, while wearing costumes that complicate this performance of gender. In one image, a man incorporates some cross dressing mixed with a seductive Marilyn Monroe-like pose revealing a man’s chest, women’s make-up and a sailor’s hat. Warren’s subjects play with these signifiers in a dynamic mash-up of projected sexual identity drawing from all columns. On and off stage, the poses are an act, but they truly express the underlying undeniable carnal macho male.

Hector Emmanuel’s beautiful black and white portrait of a musician embodies the three areas of “Macho – The Mask of Masculinity” in a single poignant photograph. Relaxed into a power stance of “cool,” bedecked with tattoos on his hefty forearms, these insignias serve as permanent props, decorating the body with a full-time “masculine” costume. Donning status symbols of a branded Polo shirt and Gucci belt, his subject’s selections signify the financial success of the wearer, with a nod to the wealthy elite and the fashion line inspired by the game exclusive to the rich and royal. The dangling decked-out rosary and cross represent - beyond the jewelry ”bling” factor for the costume, perhaps the message of being a member of the dominant Christian culture in spite of his minority race. Or is it a display of defiance? Or humility to the all-powerful spiritual “Macho” in the sky? The effect of the costume is alluring and unmistakably masculine.

PROPS

Throughout the history of art, props associated with projecting manly power included military regalia, imposing stallions, vanquished beasts, extravagant riches and deadly weapons. Michael Corigliano creates ceramic headdresses worn by his subjects that dictate the behavior of the men in his performance pieces. Who you are is represented by the symbolism in the style of hair on your head. His photographic triptych, “Stumbling” defies the typical male props and suggests that a more domestic “macho” character is emerging in this stay-at-home-dad era, in images of men with a mop in one hand, protective rubber gloves in the other--but also with a cigar and a beer. With unapologetic humor, the artist suggests a wider range of activities can be included within the extended map of self-expression and labor available to the modern man. If a counterpoint to women’s increased role in the workplace is men’s increased labor at home, Corigliano’s subjects seem to be “stumbling” with ambivalence and apprehension, towards expanded notions of gender roles.

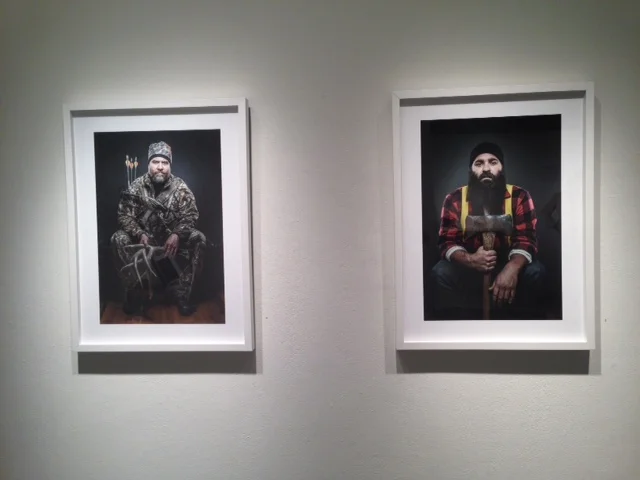

Joseph Daniel Robert O’Leary’s bold photographs of men cover a range of male props including paraphernalia from academia, business, hunting and the military, but his series “Of Beards and Men” examines the beard as a commanding marker of masculine authority. The series presents images of 150 bearded men pushing the limits of their own male identity through various shapes and styles of facial hair. While this signifier of virility is an authentic feature of male biology, in our contemporary culture, fashionable men may also wax or shave their body hair, removing it to resemble pre-pubescent boys or females. Wearing a beard therefore registers like a costume, an intentional projection of the masculine.

Timothy Johnson’s painting of a man holding a pretty pink floral plate goes beyond the women’s-work props appropriated by Michael Corigliano’s men. The title, “Breast Plate,” serves as a play-on-words, replacing the armor historically worn by men in battle with a very different kind of plate – a family heirloom. In this self-portrait, Johnson instead lovingly holds his grandmother’s dinner plate, embracing its beauty and all the references the pretty prop implies - home, food, nurturing family, decoration – all traditionally feminine nesting territory.

COSTUMES

Michael Corigliano dresses himself in three different costumes to play three different roles using everyday clothes along with his handmade headpieces to inhabit each distinct persona. Mark Newport’s cable-knit suits, on the other hand, are masks from head to toe, completely enshrouding the wearer in a costume of projected masculine power. Inspired by childhood superheroes, the artist parodies the ubiquitous comic book characters invading our adult culture, most inescapably in Hollywood. The costumes combine their heroic, protective, ultra-masculine references with soft, vulnerable personas created by the comforting gestures of a knitting mother figure. The artist embraces this historically feminine art form, and knits these figures himself. Life sized, these suits offer the promise to transform oneself by dressing up, to live a fantasy so popular it speaks to how powerless men feel in their real skin and their boardroom power-suits, unable to fight the battles of contemporary life. Conversely, the real, quotidian costumes worn by O’Leary’s bearded men and Corigliani’s slipper-clad domestic power-brokers do not always mask men’s vulnerability.

In our culture of masculinity, some men feel they have to sublimate tender and “needy” feelings into sexual desire. Boys and young men struggle to stay true to their authentic selves while negotiating America’s narrow definition of masculinity. If men and boys were permitted to own the full range of their emotions, they could take off their masks.

As the new masculinity evolves alongside, and parallel to, the growing women’s movement, it is changing in this next generation to include a wider definition that embraces fatherhood and domesticity, revealing a picture of what “Macho” might look like beyond the confines of existing masculine stereotypes. These extraordinary artists depict a continued negotiation of the conflicts in post-modern manhood and point towards a deeper expression of man’s full range of proud masculinity.