"Macho" - December 2012

Skip Brown, Paul Di Pasquale, Joel D’Orazio, Jim French, Joe Hicks, Allen Linder, Max MacKenzie, Rogelio Maxwell, Camden Place, James Rieck, Diana Williams, Charlie Sleichter

Saturday December 1st, 2012 - January 5th, 2013

Cross Mackenzie is pleased to present a group show of 12 artists whose work represents 12 distinct considerations of contemporary masculinity.

“Macho” takes as its point of departure recent debates about the role of men in contemporary society. Both the disturbing and comic evocations of our title engage with the conflicting realities of post-modern manhood. We hope that the ambiguity of the term “macho” will open up a new discussion rather than continue an old one. The work in the show does not attempt to pin down any literal definitions of masculinity, manhood, or machismo. Rather, we find in the artworks in “Macho” a variety of themes, aesthetics, and philosophies that fruitfully complicate a word that is burdened by stereotype. Violence and action stand out as two threads that weave throughout the show and begin to reveal a picture of what “Macho” might look like beyond the confines of stereotype.

In the work of Diana Williams and Paul DiPasquale, emblems of macho violence are transformed into objects of defused beauty. Diana Williams is a German-born Australian who has spent the last several years studying with master sculptors in China. Her missile sculptures are an attempt to grapple with the military past, present, and future of her family. With a husband and son in the navy, Williams’ beautiful pieces are an attempt to reconcile creation and destruction.

Joel d’Orazio’s BB Rondos similarly evoke objects of destruction, but they also resemble machines or scientific instruments. D’Orazio was a practicing architect for 25 years and indeed his works reveal an architectural relationship to objects. He works in a variety of mediums, often using found materials to create abstract but referential pieces. His BB Rondo pieces, like Williams’ missiles and DiPasquale’s archeological guns, are objects that refer to a human activity, but, in the absence of that activity, transform into still and beautiful objects of contemplation.

Ceramicist Joe Hicks’ Spark Plug forges a similar relationship between object and its imagined use. His Spark Plug transforms a banal object associated, literally, with mechanical power into a totem. Like D’Orazio’s pieces, Hick’s Spark Plug invites contemplation by disassociating itself from human activity. Rogerio Maxwell’s colorful tire prints also allude to the traditionally male world of cars and surprises us with a traditionally feminine palette. Sleichter’s subject is the mostly male world of golf.

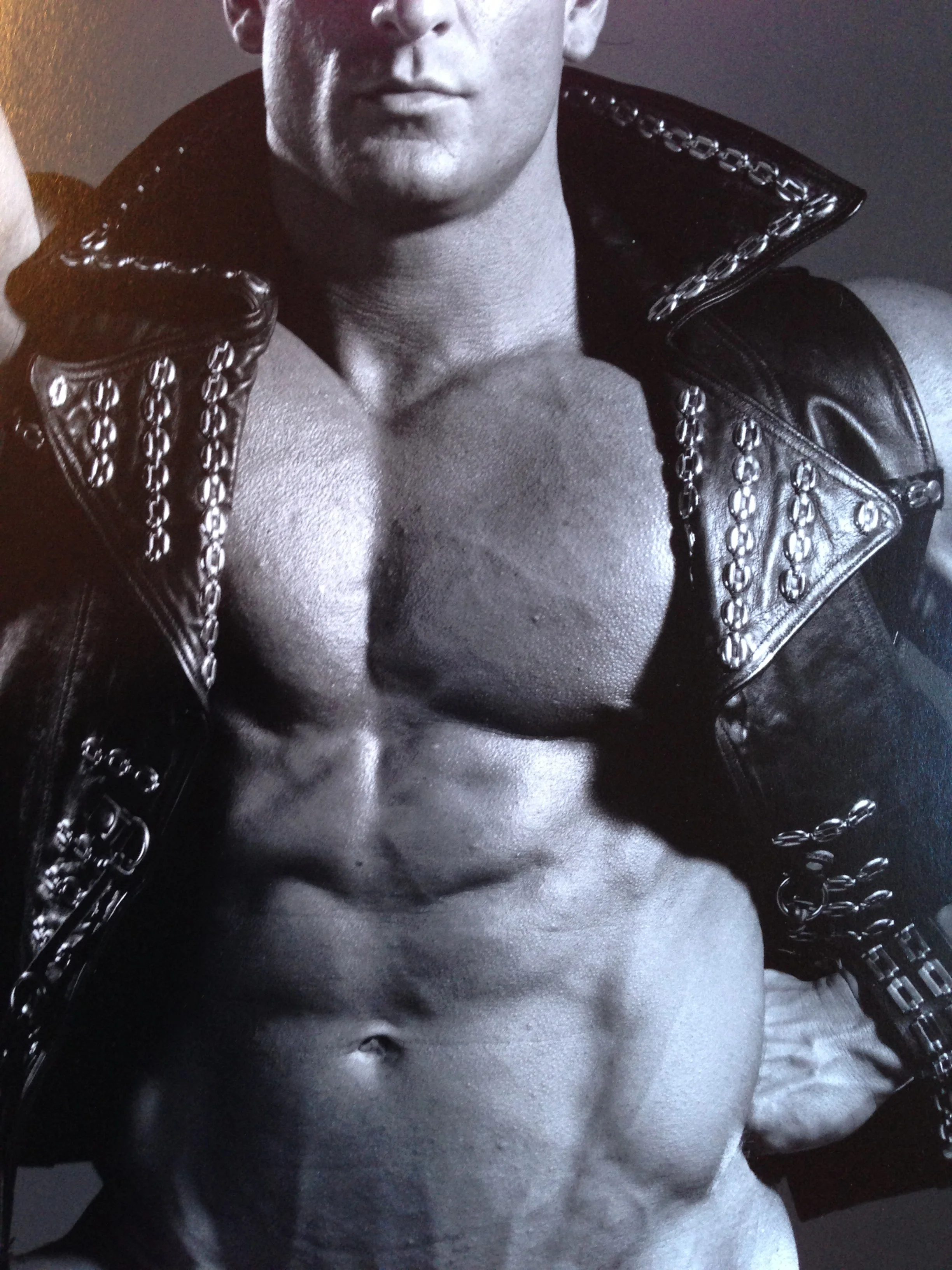

However, in the work of Skip Brown, Camden Place, and Allen Linder, it is precisely human activity that comes to the forefront. Macho physicality displayed through muscle and movement develops a human story within the work. Jim French’s robust male nudes represent the most literal interpretation of the theater of “macho” sexuality. Skip Brown’s photo of a boy posing with muscles like a strong man demonstrates this concept that “macho” as identity is an act – the action a put-on. Power-suits are put on by the power brokers in James Rieck’s impressive painting of macho boardroom power.

Brown’s extreme sports photographs capture an action into stillness, retaining all the energy of the human and natural forces at work. The kayaker and white water are equal subjects in his work, and both subjects represent an extremity of power and beauty. The powerful forces at work at not in conflict but in harmony. Similarly Max MacKenzie’s photograph through his feet while flying his ultra light, demonstrates the extremes of masculine bravery.

Camden Place, however, does create a kind of thematic conflict in his woodcarvings, by subverting the macho themes that he invokes. In “Frank and Michael Met Online,” the violence and bravado of hunting is absent, and a surprising tenderness—in the figure’s pose and the evocative title—takes their place. Similarly, “Adam’s work is never done” suggests the machismo of physical labor, but the figure is softened by his humble pose and naïve expression.

Allen Linder’s Beings are muscular figures caught in deft acts of physical strength that are surprisingly gentle and delicate. In one Being, a man rises from what is perhaps a theater seat, raises his hands to clap, his face showing a surprising expression of intensity: a normal, even cliché physical expression is turned into a comical and even unsettling physical shape. The body here is tantamount: the body, not the face, tells the story. Linden focuses on the physicality of his sculpture, and sees the physical process of sculpting as a creative process of discovery.

In fact, all the work in “Macho” has a strong sense of the physical and viewing the work is itself a physical experience of creative discovery. Machismo can be interpreted as an ésprit of action—be it extreme or even violent. In that sense, the themes of violence and activity in the work presented here form a thematic exploration of machismo but not a didactic manifestation of it. The work itself is not macho even if its themes are. Rather than forcing themselves onto their viewers, the work in the show embodies a stillness, silence, and beauty that subvert the violence, action, and extremity of its subject matter. Thus they present objects and planes for reflection, in which the viewer is encouraged to bring his own subjectivities to continue the conversation.

Camden Place

James Rieck

Diana Williams

Skip Brown

Trevor Young

Joe Hicks

Jim French